Approximately 75% of patients who present to the emergency room each year with GI bleeding have an upper GI source. Each year, 300,000 people in the U.S. are hospitalized with upper GI bleeding. Forty Four percent of those hospitalizations are for patients older than 60 years. Upper GI bleeds are considered a medical emergency and require immediate hospitalization for urgent diagnosis and treatment. Approximately 10,000 to 20,000 people die each year from upper GI bleeds.

In the United States, mortality rates from upper GI bleeds are between 3% and 7%. The earlier that an accurate diagnosis is made in patients with severe bleeding, the earlier that therapeutic treatments may be started which lowers the mortality rates.

Generally a bleed is considered to be in the upper GI tract if it is above the suspensory muscle of the duodenum called the ligament of Treitz. It connects the duodenum of the small intestines to the diaphragm near the splenic flexure of the colon.

There are many causes of upper GI bleeding including:

· Esophageal varices; (extremely dilated, sub-mucosal veins)

· Ulcers (duodenal, gastric or esophageal)

· Cancer

· Gastric varices

· Esophagitis

· Hematobilia

· Gastritis

· Vascular malformations

Patients with upper GI hemorrhage often present with hematemesis (vomiting of blood) coffee ground vomiting (the blood appears like dark coffee grounds), melena (black tarry feces), hematochezia (maroon colored stool). Patients may also present with anemia, chest pain, syncope (fainting), fatigue and shortness of breath.

The diagnosis of an upper GI bleed is assumed when hematemesis is documented. In the absence of hematemesis, an upper source for GI bleeding is likely when the patient has either a black stool or is less than 50 years old and has laboratory values of a BUN (blood urea nitrogen) creatine ratio of 30 or more. In the absence of these findings, a nasogastric aspirate will help determine the source of bleeding. Nasogastric aspirate is collected by placing a naso gastric tube through the nose, down the throat and into the stomach to remove the stomach contents. If the aspirate is positive for blood, an upper GI bleed is greater than 50%, but not high enough to be certain. If the aspirate is negative, the source of a GI bleed is likely lower. The accuracy of the aspirate is improved by using the Gastroccult test.

The presentation of bleeding depends on the amount and location of hemorrhage.Generally, the management of a GI bleed starts with an assessment of the patient to determine how much blood loss has occurred and whether the bleeding is ongoing. This is usually followed by resuscitation (replenishment of blood and fluids). The history and physical taken by the physician will usually tell the physician whether the bleeding is in the upper or lower GI tract and whether it has stopped.

On physical examination, the physician will look to the vital signs, an abdominal and rectal exam, and assessment for portal hypertension and chronic liver disease (causes of varices). If a patient is in shock, they may require immediate volume replacement. Blood tests can help determine the status of a patient.

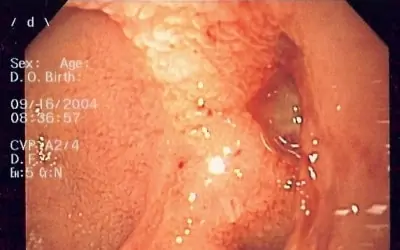

During the last ten years, most patients with upper GI bleeding undergo urgent endoscopy within 24 hours. This can not only help diagnose the source of the bleed and determine whether the bleed is ongoing, but also provide therapeutic measures to stop the bleeding through electrocautery or endoscopic clipping.